SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN ON WHITEHEAD

Stanley Yale Beach, grandson of the founder of Scientific American, son of its Editor and himself Aeronautical Editor, wrote five articles in which he credited Whitehead for having flown a powered aeroplane in 1901.

Comment:

It's hard to imagine how Orville Wright thought he could strengthen his claim to first flight by citing Beach.

Scientific American, Sept. 19, 1903, p.204

"Experiments with motor-driven Aeroplanes

...the motor was attached to the two longitudinal projecting rods of the lower aeroplane, and carried the propeller in front of it on its crank shaft.

By running with the machine against the wind, after the motor had been started, the aeroplane was made to skim along

above the ground at heights of from 3 to 16 feet for a distance, without the operator touching, of about 350 yards."

For the full article, please scroll down to the bottom of this page.

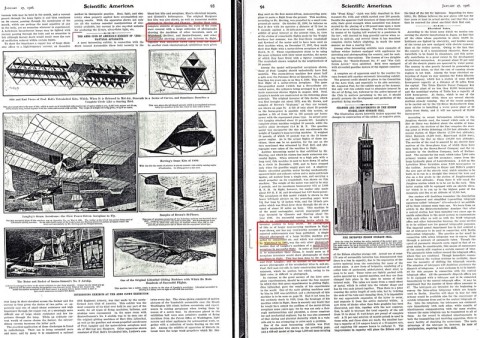

Scientific American, Jan. 27, 1906, pp.93-94

"The Aero Club of America's Exhibit of Aeronautical Apparatus

...the walls of the room were covered with a large collection of photographs showing the machines of other inventors, such as Whitehead, Berliner, and Santos-Dumont...

No photographs of this or of larger man-carrying machines in flight were shown, nor has any trustworthy account of their reported achievements ever been

published. A single blurred photograph of a large birdlike machine propelled by compressed air, and which was constructed by Whitehead in 1901, was the only other

photograph besides that of Langley's machines of a motor-driven aeroplane in successful flight."

For the full article, please scroll down to the bottom of this page.

Scientific American, Nov. 24, 1906, p.379

"Santos Dumont's latest flight

In his enthusiasm the Brazilian aeronaut forgets also that at least three experimenters in America (Herring in 1898, Whitehead in 1901, and Wright brothers in 1903) Maxim in England (1896) and Ader in France (1897) have already flown for short distances with motordriven aeroplanes, and yet no really practical machine of the kind has as yet been produced and demonstrated."

For the full article, please scroll down to the bottom of this page.

Scientific American, 15. Dec. 1906, p.447

"The second Annual Exhibition of the Aero Club of America

Whitehead also exhibited the 2-cylinder steam engine which revolved the road wheels of his former bat machine, with which he made a number of short flights in 1901."

For the full article, please scroll down to the bottom of this page.

Scientific American, Jan. 25, 1908, p. 54

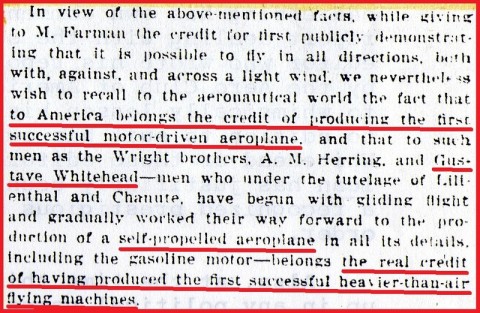

"The Farman Aeroplane wins the Deutsch-Archdeacon Prize

...while giving to M. Farman the credit for first publicly demonstrating that it is possible to fly in all directions, both with, against, and across a light wind, we nevertheless wish to recall to the aeronautical world the fact that to America belongs the credit of producing the first successful motor-driven aeroplane, and that to such men as the Wright brothers, A. M. Herring, and Gustave Whitehead - men who under the tutelage of Lilienthal and Chanute, have begun with gliding flight and gradually worked their way forward to the production of a self-propelled aeroplane in all its details, including the gasoline motor - belongs the real credit of having produced the first successful heavier-than-air flying machines."

For the full article, please scroll down to the bottom of this page.

Complete Articles:

Scientific American, Sept. 19, 1903, p.204

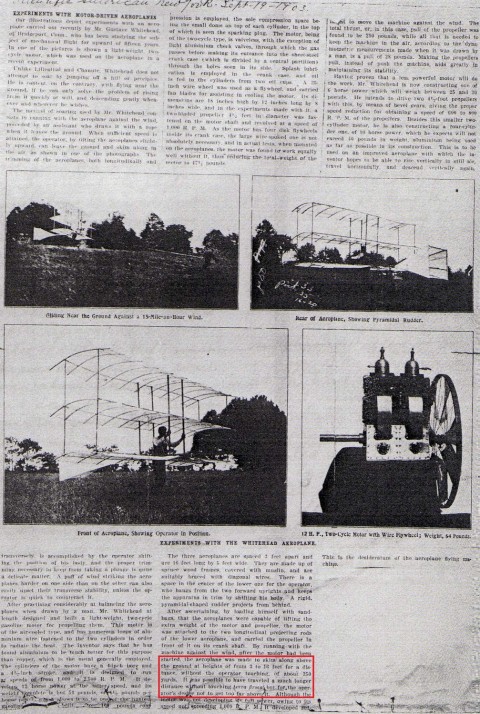

EXPERIMENTS WITH MOTOR-DRIVEN AEROPLANES

The three aeroplanes are spaced 3 feet apart and are 16 feet long by 5 feet wide. They are made up of spruce wood frames, covered

with muslin, and are suitably braced with diagonal wires. There is a space in the center of the lower one for the operator,

who hangs from the two forward uprights and keeps the apparatus in trim by shifting his body. A rigid, pyramidal-shaped rudder projects from behind.

After ascertaining, by loading himself with sandbags, that the aeroplanes were capable of lifting the extra weight of the motor

and propeller, the motor was attached to the two longitudinal projecting rods of the lower aeroplane, and carried the

propeller in front of it on its c rank shaft By running with the machine against the wind after the motor had been started,

the aeroplane was made to skim along above the ground at heights of from 3 to 16 feet for a distance, without the operator touching, of about 350 yards. It was possible to have

traveled a much longer distance without touching terra firm but for the operator's desire not to get too far above it.

Although the motor was not developing its full power, owing to its speed not exceeding 1,000 R. P. M., it

developed sufficient to move the machine against the wind. The total thrust, or, in this case, pull of the propeller was found to be

280 pounds, while all that is needed to keep the machine in the air, according to the dynamometric measurements made when it

was drawn by a man, is a pull of 28 pounds. Making the propellers pull, instead of push the machine, aids greatly in maintaining its stability.

Having proven that a less powerful motor will do the work, Mr. Whitehead is now constructing one of 6 horse power which will weigh

between 25 and 30 pounds. He intends to drive two 4 1/2-foot propellers with this, by means of bevel gears, giving the proper

speed reduction for obtaining a speed of 600 to 800 R. P. M. of the propellers. Besides this smaller two cylinder motor, he is also constructing a four-cylinder one, of 10 horse power, which he expects will not exceed 40

pounds in weight, aluminum being used as far as possible in its construction. This is to be used on an improved aeroplane with which the inventor hopes to be able to rise vertically in still air, travel horizontally, and descend vertically again. This is the desideratum of the aeroplane flying machine.