History of Whitehead Critics

Many people think aviation history is a simple, open-and-shut case where the Wrights announced they’d invented the airplane in 1903 and were celebrated by a grateful world. Even those who’ve heard of Whitehead often think he was a spoiler who only showed up later claiming a 1901 flight. In fact, it was the other way round. The Wrights didn’t release photos of their flight until 1908. Before that, Whitehead had been celebrated across America as the inventor of the aeroplane.

Elsewhere, it was a different story. Existing aviation histories were written in the context of two World Wars and a Cold War where aircraft were decisive weapons. So, until recently, historians in each country had the job of securing first-flight honors for their native sons. The claims of Mozhaysky (Russia), Jatho (Germany), Ader (France), Pearse (New Zealand), Vuia (Romania), Kress (Austria), Santos-Dumont (Brazil), Hargrave (Australia), Watson (Scotland) and Maxim/Pilcher (England) are all supported to varying degrees by national historians, depending on the level of patriotic fervor in their respective homelands.

The USA is a good example of how history was written in Wartime. It wasn’t until early 1942, just a few months after the USA entered World War 2, that American historians at the Smithsonian Institute finally decided the Wright brothers from Ohio had made the first, powered aeroplane flight, culminating in a permanent Wright exhibition 6 years later.

Since the Cold War ended, the world has gradually entered a post-national age. Compiling a global history has necessitated revisions. (For example, Vikings, not Spaniards are now held to be the discoverers of the New World.) And there can’t be a dozen people who all invented the airplane. Information technology is accelerating this process. These days, people don’t rely on editors or historians. If they want to know what happened in 1901, they simply read 1901 newspapers online. Other factors contributing to an expansion of aviation knowledge are Freedom of Information Laws and the expiration of Wartime secrecy statutes.

This is the context for a study of Whitehead critics. Their history is almost as fascinating as the history of Whitehead himself…

Critic No. 1: Orville Wright

Whitehead critics first emerged as a result of the 1937 release of Stella Randolph’s book, “Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead”. A groundswell of popular outrage had spread across the USA demanding recognition of Whitehead. Even mainstream journals like Reader’s Digest and popular radio shows like "Famous First Facts" were piling onto the Whitehead bandwagon. So in August 1945, while WW2 was still raging against Japan and just three years prior to his death, Orville Wright, an old man struggling to save his legacy, chose a US military magazine to attack the German, Whitehead. (Orville’s brother, Wilbur, had withdrawn years earlier, planning to study theology, but spent most of his time with law suits. He'd wanted to be a preacher like his father but died of an infectious disease in 1912.)

Not only did Orville write a scathing and wholly inaccurate article attacking Whitehead. He also resorted to his previous method of securing recognition – lawyers. Just months after the pro-Whitehead article in Reader’s Digest hit the newsstands, Orville demanded a secret contract from the Smithsonian Institute. The gist of the contract was, if the Smithsonian would guarantee in writing that he and his brother would always be recognized as the inventors of the airplane, he would give them his repaired “Flyer” aircraft which had been on display in London. The contract was signed and is still valid.

Acting on a tip from Whitehead-researcher, Maj. O'Dwyer, a US

Senator used the post-Watergate Freedom of Information Act to force the Smithsonian to admit the contract’s existence. To this day, the terms of employment of all employees of the Smithsonian

Institute require them to say the Wrights flew first (a scandal reaching far beyond the history of aviation – negotiated history?)

The arguments espoused by Whitehead critics derive mostly from Orville Wright’s 1945 article. Although the article represents the opinion of a party and therefore has no evidentiary weight, they quote it as zealously as others quote bible verses.

Wright relies on Dvorak, Beach and a Bridgeport resident named Dickie, all of whom state they weren’t present at Whitehead’s 1901 flight and two of whom didn’t even know Whitehead at the time. Wright quotes Dickie as denying “the aircraft” ever flew but neglects to mention, Dickie was being shown a photo of a ground-based engine test-bed at the time (and being asked if it was “the aircraft”). He also neglects to mention that Dickie had lost money he’d invested in Whitehead. Wright quotes Beach denying Whitehead flew, but neglects to mention, Beach never signed the statement from which he quotes (which Wright had arranged to have prepared for Beach). Wright also neglects to mention, Beach had indeed published five articles confirming pre-Wright powered flights by Whitehead. And when Wright quotes Dvorak, he selectively cites Dvorak’s disappointment at Whitehead’s rejection of his motor design rather than the front-page article Dvorak wrote praising Whitehead’s technical prowess.

Wright then ignores the 17 eyewitness statements, most of them made under oath, of persons who attested they were indeed present and saw Whitehead fly, dismissing them in unflattering terms as unqualified because those making them were either old, housewives or foreigners. He neglects to mention, none of the persons who claim to have seen himself fly in 1903 ever signed anything, let alone under oath.

Wright goes on to dismisses the validity of the journalist’s eyewitness report which appeared in the Bridgeport Herald in August 1901, while neglecting to mention, he himself didn’t invite any journalists to witness his own, claimed first flight in 1903. He also neglects to mention that when he did invite 60 journalists in May 1904, he failed to fly for three days and the journalists left, convinced he was lying.

Wright’s main argument for dismissing the report is that – according to him – no-one took any notice. He claims, no other newspapers anywhere picked up the story indicating everyone thought it was a hoax.

Apart from the fact that “popular acclaim” never qualifies as “proof” (only evidence does) and “not reporting” something isn’t equatable with “rejecting it as a hoax”, Wright was completely wrong. The world had to wait 110 years until the Information Age exposed his lie. This author found the first 15 Whitehead articles by simply entering the search phrase “Gustave Whitehead” in the Library of Congress Newspaper Search Archive. Entering “Whitehead Bridgeport”, “Whitehead flying machine”, “Whitehead airship” and so on – there and on other sites around the world – yielded a total of 136 contemporary articles about Whitehead’s 1901/2 flights. There are certainly many more articles out there. But, applying Wright’s own “logic”, 136 articles would “prove” Whitehead flew. Of course they don’t prove anything. Neither would an article which reported it was a hoax have any probative value – unless it quoted a witness*. However, what they do prove is how faulty both the purported “facts” and the arguments which Wright offered were.

Wright’s biggest blooper was suggesting the newspaper itself considered the story a lark because it waited

four days before publishing it. Again, Wright was making it up as he went along. It was a weekly newspaper which published a full-page report in a special section of its very next edition. In this

regard, it's notable that the first eyewitness report by a journalist who witnessed a flight by the Wrights appeared on page 36 of a beekeeper's journal 102 days (7 editions) after the flight took

place. [That article was headed by drawings of a church and a child reading the Bible. Interestingly, Wright cites

drawings of witches heading the report of Whitehead's first flight as "proof" it wasn't meant to be taken seriously. However, Wright must have known that witches were a

widely-used luck-symbol in early aviation. Ultimately, any suggestion the article was meant as a joke was disproven when, in 1937, the newspaper's publisher reprinted the article, stating, it

stood by its story and opening its archives to investigators from both Harvard University and The Library of Congress - in each case professors who independently concluded, Whitehead had flown

first.]

Critic No. 2: Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith

The next Whitehead critic to emerge was Britain’s Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith. Gibbs-Smith had been a plane-spotter for the RAF during World War 2 with the job of identifying enemy (German) aircraft. His interests also included tapestries, photography and 19th Century women’s fashions. However, what he’s best known for is his interest in the paranormal (ghosts) and flying saucers.

In a famous January 23, 1966 interview, Gibbs-Smith stated on public television, he had determined a recent UFO sighting was “an interplanetary vehicle” and that information about UFOs was being “suppressed by higher-ups in Whitehall and Washington”. Since then, he’s been glorified by two generations of conspiracy theory fans, although he was quickly proved laughably wrong. [An airline passenger had filmed „a UFO“ through the plane’s window. But on closer examination, it turned out to be the plane’s tailplane reflected in the prism-like border of the window.] Gibbs-Smith's “Whitehead determinations“ are of a similar quality.

Gibbs-Smith apparently got involved in the Whitehead-controversy at the behest of his employer. At the time Major William O'Dwyer's book about Whithead appeared, Gibbs-Smith was working both for the Smithsonian Institute (as the first awardee of the 'Lindbergh Chair' for his research on the Wright brothers) and for the Science Museum in London (which is where the Wrights' "Flyer 1" had previously been on display). In both capacities, he was suddenly flung to the forefront of efforts to champion a rebuttal.

Gibbs-Smith’s review of Whitehead’s work is barely more than a rehash of Orville Wright’s 1945 tirade. One argument he added is how – according to him – Whitehead implicitly admitted never having made a powered flight because when he finally applied for a patent in 1905, it was only for a glider. Taking this argument to its logical conclusion, this would mean the Wrights never flew either. After all, their first patent was also for a glider. Another argument Gibbs-Smith added was to assert that in 1901 no acetylene engine existed, which is totally false. A French company, Air Liquide, even had international dealerships set up for their acetylene engine with a branch office in Bridgeport. And two years previously (1899) acetylene-powered automobiles were offered for sale. Indeed, Whitehead's achievements were heralded in the acetylene industry's contemporary trade journal, "l'Acetylèn".

Gibbs-Smith’s review of Whitehead’s work was so devoid of facts, the Smithsonian itself, which had commissioned it, elected not to publish it. It’s not known if Gibbs-Smith’s utterances about flying saucers and Washington conspiracies played any role in their decision.

In an attempt to explain why his work on Whitehead was never published by the Smithsonian, in 1970 Gibbs-Smith wrote: “In 1968 I offered to write [ ] – without fee – the official monograph on Whitehead. [ ] But in the unsavoury atmosphere that has now arisen, I have felt it is my duty to relieve the Museum of their acceptance of my offer [ ]. Some member of Congress might have [ ] inquired why [ ] a bigoted old English historian writes about one of Connecticut’s most favoured sons.” It was only ever published in a German magazine.

As the world's No. 1 conspiracy theorist on flying saucers, Gibbs-Smith also gave the world the following conspiracy theory:

- four independent newspapers conspired over a period of five years to describe a "non-existant" 1901 photo of Whitehead in motor-driven flight;

- 134 newspapers around the world conspired to report that Whitehead had achieved "a mythical" motor-powered flight;

- 17 independent witnesses, from Pittburgh to Bridgeport, secretly banded together to falsely attest - under oath - to having seen Whitehead fly a motor-driven aircraft prior to 1903, "all of whom were either lying or having apparitions"; and

- almost all the leaders of the pre-1912 US aeronautical community conspired to leave "false" evidence indicating they'd worked with Whitehead.

Gibbs-Smith's "method" was by no means limited to his "study" of Whitehead's career. In a 1956 letter to FLIGHT Magazine, Gibbs-Smith opined that the Wrights would never have obtained their patent if a 1868 Patent by Boulton had been known of at the time. Clearly, he was making it up and had never bothered to check. The Boulton patent was a core issue in the Wright vs. Herring-Curtiss Co. proceedings.

Following in Gibbs-Smith's footsteps came the next Whitehead-critic, Tom Crouch, who in his 1981 book, "A Dream of Wings", acknowledged "an enormous debt" to Gibbs-Smith in the study of Whitehead's career...

Critic No. 3: Tom D. Crouch, Ph.D.

It's impossible not to feel the greatest sympathy for the diligent staff historians at the Smithsonian - a prominent center of scholarship. That's because in the matter of "first aeroplane flight" they find themselves condemned to quote verbatim - under threat of legal action - from Orville Wright's own version of Orville Wright's maginificent contribution to aviation. In a situation unparalleled in the annals of historical scholarship, a previous generation of Smithsonian trustees has forbidden its successors from ever questioning or investigating a crucial aspect of aviation interest. Consequently, when reading the Smithsonian's pronouncements on early aviation pioneers, it's impossible to know what's been distilled from painstaking research and what's been dictated by Wright's writ-waving attorney. Once research becomes tainted in this way, even accurate passages are under a cloud of suspicion.

Today, the most distinguished holder of this poisoned chalice is Tom D. Crouch, Ph.D.. Crouch has been a historian at the Smithsonian Institute since 1973. In fairness, before examining his statements about Whitehead, it's important to point out that his terms of employment expressly forbid him from ever stating anyone else flew before the Wrights (otherwise he'd subject his employer to damages of a severity he himself describes as "priceless".) Here's the exact wording of the contract, as set down by Orville Wright's attorney:

“Neither the Smithsonian Institution or its successors nor any museum or other agency, bureau or facilities, administered for the United States of America by the Smithsonian Institution or its successors, shall publish or permit to be displayed a statement or label in connection with or in respect of any aircraft model or design of earlier date than the Wright Aeroplane of 1903, claiming in effect that such aircraft was capable of carrying a man under its own power in controlled flight.”

As mentioned above, Tom Crouch of the Smithsonian was the next Whitehead critic to tread in Wright's and Gibbs-Smith's footsteps. He describes himself as "owing an enormous debt to Mr. Gibbs-Smith for his guidance in the study of Whitehead's career". In the Foreword to his Whitehead-critical 1981 book, “A Dream of Wings”, he reverently refers to the discredited Gibbs-Smith as a “Doyen of early aeronautical history” and thanks him and other mentors for answering his “naïve questions on aerodynamics and aircraft structures”(p.9).

In "A Dream of Wings" Crouch disposes of Whitehead early on by writing, “Whitehead left Boston in the spring of 1897. [ ] After his departure, the German was to remain apart from the mainstream of the aeronautical community, too independent and eccentric to ally himself with an established group again.” He added, “Whitehead’s work drew no attention from knowledgeable authorities. The occasional brief newspaper story or article in an obscure mechanic’s magazine suggesting that Whitehead had been very busy during the years 1897-1902 was completely discounted.” (p.119). The blatant erroneousness of this statement is demonstrated not only by the almost 500 newspaper articles found so far but also by the Smithsonian itself: Its Bibliography of Aeronautics, issued 1910, mentions Whitehead and his aircraft eleven times. (The Smithsonian can't be dismissed as not being a “knowledgeable authority”.) Indeed, 31 years later, Crouch contradicted it himself in the draft of a 2012 article he wrote about a 1908 aviation event for NY Magazine. In it he writes, "Whitehead was, at the time, a well-known builder of engines and airframes".

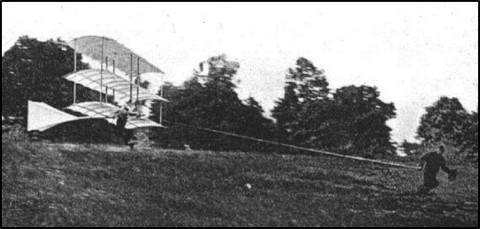

Crouch reserves his most derisive comments for Whitehead’s aircraft, stating: “News photos that appeared at the time of the alleged flight show an incomplete craft missing the engine” (Dream of Wings, p.122). This seems to refer to the picture (below) which is known to have appeared in thirteen contemporary publications. Whitehead's aircraft had two engines. He had simply detached one of them (the wheel motor) to show it to the camera. The other (propeller) motor is clearly visible in the background. Crouch appears not to have grasped the sophistication of Whitehead's design and maligned it as a result.

A further criticism of Whitehead's machine is that it was was structurally too flimsy. As supposèd proof, the “knowledgeable opinion” of Charles Manly is quoted. Elementary research, however, would reveal that Manly never saw Whitehead’s machine; he’d merely been told about it by a Mr. Traylor, an administrative clerk with no mechanical expertise, who worked at the Smithsonian (Prof. Langley's Personal Secretary). A further fact which a fastidious historian might consider worthy of mention in this connection is that Mr. Traylor had only seen it dismantled in its packing crate when it arrived by rail in Atlantic City.

Besides pointing out that no photos of Whitehead’s claimed flights exist, Crouch’s main argument appears to be that, later, non-successful aircraft (which he attributes to Whitehead but were, actually, aircraft designed by his customers for his engines) somehow 'proved' that Whitehead’s earlier attempts had also been unsuccessful (Dream of Wings p.125). Such circumstantial arguments are non-conclusive. There’s no obligation for an inventor to continue inventing once he believes he’s solved the problem he’d set out to solve, or to pursue costly experiments – especially if he’s broke and has a young family to support. (Augustus Herring, for one, is a good example: He got his aeroplane to fly then stopped inventing and teamed up with Glenn Curtiss.)

Even if all these contested assumptions somehow applied, the basis of the argument is at odds with the facts. Whitehead did make a powered flight in 1903 by attaching a small, lightweight motor to his old, tri-plane glider from his New York days (which was all he had left after Linde had forced the closure of his workshop). Two months before the Wrights claim to have flown, its flight was reported in the Sept. 19, 1903 edition of Scientific American (p.204): “The aeroplane was made to skim along above the ground at heights of from 3 to 16 feet for a distance, without the operator touching terra firma, of about 350 yards.” Photos of both the aeroplane and the motor accompanied the article.

In the April 22, 2003, edition of The Baltimore Sun, Crouch accuses Whitehead supporters of harboring "conspiracy theories". A "theory" is unproven, but when it comes to anti-Whitehead bias at the Smithsonian, there's actual proof:

- In Sept. 1901, Smithsonian employees Traylor, Hodge and Manly conspired to

secretly measure Whitehead's aircraft (presumably at the behest of the

Smithsonian's Director).

- In a letter to Whitehead researcher, Maj. William J. O'Dwyer (USAF)

dated Sept.

12, 1968, Smithsonian Director Johnstone wrote: "We have no mandate to sit

in judgement on, nor to endorse, nor to detract from anyone's

accomplishments either by implication or by direct action". Subsequent

exposure of the then-secret Wright-Smithsonian contract proves this statement to

be the diametrical opposite of the truth.

- In early May, 2012, the editor of this website was hired to

appear in a two-part,

Smithsonian Channel documentary as their expert on roadable aircraft. He himself

witnessed supression of pro-Whitehead evidence. During filming, in July 2012, the

producer told him that pressure from Smithsonian historians had forced her to

delete all mention of Whitehead from the documentary, despite clear and

convincing evidence that his was the first roadable aircraft.

- The following letter by World War I aviation historian, Leo Opdyke, to Whitehead's

Great Grandson, Curtis Mitchell, might be construed to suggest the Smithsonian's

Chief Historian, Tom Crouch, has had a photo of Whitehead's No. 21 in flight since

at least 2005 without publicizing it:

- Finally, in a 1982

interview for Bavarian television, Crouch stated he’d “visited

every museum in the world which has information about Whitehead”. However,

neither the Whitehead Museum in Connecticut nor the one in Bavaria is aware of

having been visited by him. Thus, when he writes, “The best efforts of Whitehead’s

supporters have failed to provide any of the answers” (A Dream of Wings p.126), it

may have been because he never asked any questions. Even on Sesame Street,

kids learn, “if you don’t ask, you won’t know”. That may be a good place

for Government historians to start when writing a post-national history of aviation

for a transparent world.

Sadly, until the legal agreement with Wright can be safely abrogated, there will always be suspicion that supportable fact and Orville's self-serving fiction have become inextricably intermingled in the Smithsonian's pronouncements on this key period in the development of aviation.

How did all this happen?

Many factors – not just the lack of a photo – contributed to how and why Whitehead was denied recognition for the first powered flight. Some of them were major events. But - as is often the case - simple human failings appear to have been the prime cause.

It all started with Prof. Samuel P. Langley, who was in the remarkably contradictory position of being both an aspring aircraft inventor and Director of the Smithsonian Institute, respondible for documenting the activities of other aircraft inventors. Langley had a special kind of personality. He insisted his workers walk behind him. His staff complained of mistreatment due to his “extremely impatient, nervous prostration” and him being “a demanding perfectionist who insisted on absolute obedience”. Others also complained about Langley’s demeanor. For example, Otto Lilienthal described him as “haughty” when he visited him in Berlin.

Langley was determined to be the first person to fly. His personality shone through in this pursuit too:

- In a memo describing flights by Lilienthal, Langley wrote, “I did not feel that I learned much”; [the reader recalls, neither Langley nor his aircraft ever flew]

- Augustus Herring and Langley had such great personal differences that their working relationship ended after only seven months. Aside from the personality issues, Herring's main complaint was Langley’s “inability to distinguish between ideas of others and his own”. Indeed, a Washington reporter accused Langley of stealing the ideas of others.

- Langley was unwilling to publicize the results of his experiments.

- Langley instructed 3 staff-members to spy on at least one other inventor (Whitehead).

None of this behavior is compatible with that of a museum director.

A museum is entrusted by the public to impartially collect information for posterity. To this end, it approaches inventors, typically gaining their trust and in turn being provided with information and exhibits. Denigrating inventors (as with Lilienthal), stealing their ideas (as with Herring), withholding information (as at the Chicago Aeronautical Conference) and spying on inventors (as with Whitehead), all the while competing with them in an attempt to invent something first, is clearly inappropriate. On top, Langley spent several hundred thousand dollars of taxpayer’s money on his failed experiments, giving him an unfair advantage (and also incurring massive criticism from Congress).

Langley finally declared victory and quit. He claimed his aircraft had flown when, in fact, all it had done was unceremoniously plop into the Potomac River. (It fell off the end of its launch rail - mounted on a ship - during an attempt at takeoff.) In one of the longest court cases in American history, the Wrights proved Langley’s invention hadn’t flown. However, during the hearings and even beyond (throughout WW1 up until 1928), the Smithsonian Institute continued to display Langley’s aircraft with a plaque stating it had been the first to perform manned, sustained, controlled flight.

Only after the case ended did the Smithsonian start coming to terms with the Legacy its former Director had bestowed upon it. The situation was embarrassing. By indulging Langley’s egomaniacal personality for so long, credibility had been lost.

The Museum tried to find a new direction. However, none of the leaders of the aviation community wanted to have anything to do with it. Glenn Curtiss was still upset about the position it had taken during the court case. Orville Wright simply boycotted it, sending his “Flyer 1” to England for display there. Even the Library of Congress across the street was furious. Its expert, Prof. Albert Zahm, a trained aeronautical engineer and himself one of the first people to build and fly a glider in America, vehemently disagreed with the Smithsonian’s position. The Smithsonian therefore spent several years apart from the mainstream of the aeronautical community, too independent and self-righteous to ally itself with any major grouping.

Two events of adversity were to make strange bedfellows. Firstly, in 1938, Hollywood filmmakers and in 1941, Reader’s Digest, along with much of the mainstream US media started demanding recognition of Whitehead as the first to have achieved powered flight. Suddenly, Orville Wright had a problem. He needed recognition in the USA and could no longer afford to continue his boycott. That meshed well with the Smithsonian’s own search for renewed relevance. Secondly, in December 1941, the USA was plunged into war with the axis powers (Japan, Germany and Italy). The likelihood of a German now being declared the first to have flown was – to say the least – reduced. Besides, the public was distracted. The Wrights’ recognition took place a few months later.

For the Smithsonian, it was an easy call. A Supreme Court decision had confirmed the Wrights as inventors of key components of the aircraft (albeit, without examining Whitehead’s case). Furthermore, then as now, no serious historian – including this editor of this website – doubts that the Wrights were the best among their peers in the early days of aviation. They showed up in Paris in the summer of 1908 flying rings around stadiums while most other inventors were struggling to stay aloft briefly when flying in a straight line. However, although they were the best, they weren’t the first.

The invention of the airplane is comparable in some ways to the invention of the personal computer or the smartphone. Bill Gates and Steve Jobs patented and litigated until they dominated the market. But that doesn’t make them the inventors of these products. With the Wrights it’s a bit different inasmuch as they did actually develop certain things. However, rather than improve aircraft design, their patents forced American aviation backwards, away from the modern wheeled, monoplane, empennage, tractor-propeller which was widely used and “open source”.

Shifting its support from Langley to the Wrights was an act of expediency and not the result of diligent, historical research. Rapproachment with Wright brought the Smithsonian a reward of inestimable value: Orville authorized repatriation of the Flyer No. 1 from London to Washington DC, where it remains to this day. However, the switch of the laurel wreath was negotiated, not investigated. Whitehead’s biographer, Stella Randolph, was shunned by the Smithsonian although she worked right in Washington DC. Prior to recognizing the Wrights, no attempt was ever made by the Smithsonian to secure Whitehead’s engines, aircraft, photos or documents or to examine his claim.

Further to securing the Flyer No. 1, the Smithsonian had to agree to the draconian terms specified in the legal document quoted above. For obvious reasons, its very existence was kept secret and wording had to be extracted - eventually - under Freedom of Information law. Interestingly, Wright (or his attorney) tried to be too clever when tying up the Smithsonian, and the latter's trustees, apparently, failed to notice the blunder: By referring to "any aircraft" and not "airplane", the document prohibits the Smithsonian from even admitting that, since 1852, dozens of dirigable airships (indisputably 'craft of the air') had been "capable of carrying a man under [their] own power in controled flight". Count Zeppelin and his predecessors would be as unhappy as Whitehead if airbrushed out of history by this secret agreement.

It took the Smithsonian four decades to admit it was wrong about Langley and transfer its allegiance to the Wrights. It may be argued that the correct course of action for any museum would have been to conduct thorough investigation first. Inventors aren’t “declared” or “negotiated” but determined based on hard evidence. How long will it take with Whitehead?

For a different perspective on how the Smithsonian handles aviation history, read another view here.