New York Telegram, Novemer 19, 1901, p.10

Transcript.

Direct quotes of statements by Whitehead in bold italics (see below):

10 THE EVENING TELEGRAM – NEW YORK, TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 19, 1901.

SHIP THAT WILL FLY LIKE A BIRD MAY SOON BE PLACED ON THE MARKET

Model That Has Traveled Mile and Half in Air Being Rebuilt at Bridgeport.

Gustave Whitehead, Backed by Capital, Has Seventeen Machinists at Work in Little Shop.

ENGINE FINEST IN WORLD

Winged Boat Made to Speed on Land and Sail in Water Also.

[SPECIAL DISPATCH TO THE EVENING TELEGRAM.]

BRIDGEPORT, Conn., Tuesday.–The sight of flying machines flapping their wings, as they glide through the air over hill and valley and above

the busy life of city streets, is soon to become a reality. Inside of a year one may be able to purchase an air vehicle and tour about in it through space as freely as automobiles are used to-day.

This may read like a dream, but it is reality, for in this city a young man is building a machine, the counterpart of which has already journeyed for a mile and a half through the air. And what is

more, the new machine will be able to travel on land at great speed and also through the water.

The inventor is Gustave Whitehead. With seventeen skilled machinists working under him in a little shop in Pine street, on the outskirts of

this city, he is working night and day on the machine, the likes of which he expects before long to have in the market. It is not an experiment nor the creation of a dreamer, for Whitehead has

already built an air ship resembling a huge bird, which has proved that he has solved the problem of aerial navigation.

Santos-Dumont has traveled through the air around the Eiffel Tower in Paris, but as Whitehead says, his is not a flying machine but a floating

machine. The machine of Whitehead will not float like a balloon, but will soar through the air without the aid of any gas to keep it up.

”This new machine will be the twentieth I have made“, Whitehead said as he

mused in his work to-day, and talked about the invention that promises to make him famous for all time, „Eighteen of them were failures, through some small fault that I could not fathom at the time,

but the last one I made rewarded my years of effort and accomplished what I have so long been trying to solve.

----------

Will Astonish World.

“The new one I am making now will be far better than the last one. For I have profited by my

mistakes and, when completed, it will astonish the world. It will have the finest engine ever made, one I invented and constructed myself, and its power, considering the weight, will be far greater

than that of any engine in existence.

“Since I was a boy, going to high school in Augsburg, Germany, where I acquired some knowledge of

mechanics and engineering, I have had the idea of a flying machine in my mind and then I made up my mind that I would some day be like the birds I was so fond of watching. After leaving school I went

to sea and sailed around the world five times.

“I remember once watching the big condors flying off the South American coast and trying to

understand how they did it. I used to study the gulls too, as they would soar against the wind with outstretched planes moving apparently without the slightest effort.

“Now I understand how they did it, for I have done the same thing myself. I am the only man who has

ever risen from the ground and have flown through the air. Money? No, I do not believe I will ever be rich. At least I do not think or care to think about that. When I make my machine perfect so I

can fly about at will, I shall be satisfied. My new machine will do that better than the old one, but, of course, there will always be room for improvement. Besides flying through the air, it will

run along the ground on four big rubber tired wheels and will also sail through the water.

---------

Mile a Minute.

“I expect my new machine to attain a speed of fifty or sixty miles an hour through the air and

about forty miles and hour on the ground. The little propeller astern, which will be arranged so it can be connected with the land engine, will drive the machine through the water at a speed of

something like fourteen miles and hour. The power will be generated by calcium carbide, which is fourteen times as powerful as gasoline.”

With all his knowledge, Whitehead is a modest man. When I surprised him in his shop, he at first refused to talk about his invention at all,

saying he would rather wait until the new machine was completed. He declared, however, there was no secret about what he was doing and to prove it pointed out a window and said:--

“There is the machine that I flew in. You can go out and look at it. It is abandoned now as junk for

the new one I am making will be much lighter and stronger and will contain better material. The old one taught me my lesson, and that was enough for it to do.”

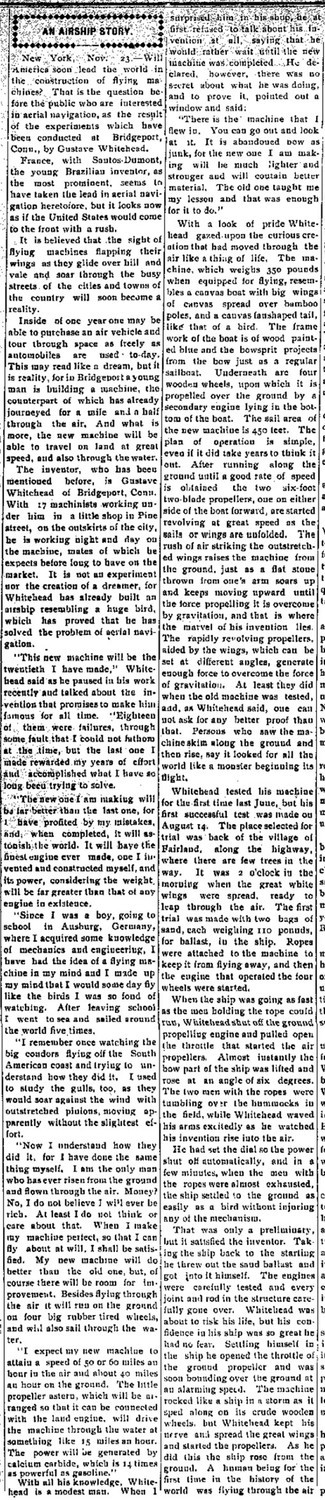

It was with a look of pride that Whitehead gazed upon the curious creation that had moved through the air like a thing of life. The machine,

which weighed three hundred and fifty pounds when equipped for flying, resembles a canvass boat with big wings of canvas spread over bamboo poles, and a canvass, fan-shaped tail like that of a bird.

The framework of the boat is of wood painted blue, and a bowsprit projects from the bow just as in a regular sailboat. Underneath it are four wooden wheels upon which it is propelled over the ground

by a secondary engine lying in the bottom of the boat. The sail area of the old machine is 130 feet. The idea of operation is simple, even if it did take years to think it out. After running along

the ground until a good rate of speed is obtained, the two six-foot, two-blade propellers, one on either side of the boat forward, are started revolving at great speed and the sails or wings are

unfolded.

The rush of air striking the outstretched wings raises the machine from the ground just as a flat stone thrown from one’s arm soars up and

keeps moving upward until the force propelling it is overcome by gravitation.

----------

Like a Wild Goose.

Unlike the flat stone, Whitehead’s machine does not yield to the force of gravitation and that is where the marvel of his invention lies. The

rapidly revolving propellers, aided by the wings, which can be set at different angles, generate enough force to overcome the force of gravitation. At least they did when the old machine was tested,

and, as Whitehead says, one cannot ask for any better proof than that. Persons who saw the machine skim along the ground and then fly, say it looked for all the world like a monster wild goose

beginning its flight. Whitehead tested the machine for the first time last June, but his first successful test was made on August 14. The place selected for the trial was back of the village of

Fairfield, along the highway, where there are few trees in the way.

It was two o’clock in the morning when the great white wings were spread, ready to leap through the air. The first test was made with two bags

of sand, each weighing 110 pounds, for ballast, in the ship. Ropes were attached to the machine to keep it from flying away, and then the engine that operated the four wheels were started.

When the machine was going as fast as the men holding the ropes could run, Whitehead shut off the ground propelling engine and pulled open the

throttle that started the air propellers. Almost instantly the bow of the ship was lifted and rose at an angle of six degrees. The two men with the ropes were tumbling over the hummocks in the field

while Whitehead waved his arms excitedly as he watched his invention rise in the air.

He had set the dial so that the power shut off automatically, and, in a few minutes when the men with ropes were almost exhausted, the ship settled to the ground as easily as a bird without injuring any of the mechanics.

That was only a preliminary test, but it satisfied the inventor. Taking the ship back to the starting point, he threw out the sand ballast and

stepped into it himself. The engines were carefully tested and every joint and rod in the structure carefully gone over.

Whitehead was about to risk his life, but his confidence in his ship was so great he had no fear. Settling himself in the ship, he opened the

throttle of the ground propeller and was soon bounding along the ground at an alarming speed.

The machine rocked like a ship in a storm as it sped along on its crude wooden wheels, but Whitehead kept his nerve and soon spread the great

wings and started the propellers. As he did this the ship rose from the ground. A human being, for the first time in the history of the world, was flying through the air like a bird. Up the ship

soared until it was about fifty feet from the ground and making a “chunk, chunk” something like the noise of a threshing machine. Everything was working just as the inventor had planned it

should.

But there was danger ahead, for the ship was moving straight at a clump of chestnut trees on a little knoll. Whitehead saw the danger, but

seemed powerless to avoid it, as it was too late to rise above the trees, high up on the knoll as they were, and the inventor had not thought of a plan to turn suddenly sideways. To strike the trees

meant destruction to the airship and probable death to its solitary passenger. But neither happened. Whitehead suddenly remembered how birds slanted their wings when they turned, and instinctively,

he turned a little to one side.

This curved the ship and she turned her nose away from the trees and glided around them as prettily as a steam yacht answers her helm. This

gave Whitehead confidence, and he looked back and waved his arms. He had now soared through the air for more than half a mile and, satisfied with what he had accomplished, shut off the power.

Without a slip or any indication of turning over, the ship settled down from a height of about fifty feet and lighted on the ground so gently

that her passenger was not even jarred.

Another trial was made later and the ship sailed through the air for a mile and a half without any accident. But all that is in the past, and

Whitehead now has his eyes and mind turned to the future. The new ship – but before going into that, it will be interesting to tell something about this remarkable man who has conquered the eternal

force of gravitation.

Whitehead is only twenty-seven years old, and he was born to Bavaria. To prove that he is an American at heart, however, aside from speaking

excellent English, he dropped his real name, Weiskopf, about six months ago, and adopted the same he now uses. He came to New York a few years ago and, while working in a humble way, began making

models of flying machines.

They were not successful. He refused toknow what despair was, however, and, three years ago moved north to Buffalo, where he was married. More

machines were made there, but Whitehead could not make them fly. From Buffalo he went to Pittsburg, Pa., where he kept on working and trying. He made a machine in Pittsburg which,

as he says, was more or less successful, but chiefly less, though improvement over former ones. About a year and a half ago he came to Bridgeport.

As he said to-day, he had no means to build the new machine he had in his mind then, but instead of giving up, he took a position as night

watchman and worked day-times in a cellar building the ship that has crowned his efforts with success.

His savings were meager, and he used all on the machine, but the future looks brighter now, as Whitehead has a man with capital backing him.

Who the man is Whitehead refuses to say, and he was equally non-committal in talking about his plans for the future. But he admitted that his machine would be put on the market in a few months

perhaps and said it was possible that the price would be as low as $1,500 or $2,000.

---------

Common as Automobiles.

“I have no doubt flying machines will be as common as automobiles in a few

years“, Whitehead said, “and before you and I are old men there will be more travelling through the air than on land or water. At

present it seems impossible that air ships will be able to carry heavy cargoes or even many people. I say it seems improbable, but it is not impossible.

“It is not safe nowadays, when so many wonderful things are being invented, to say anything is impossible. I am not prepared to say something is impossible except

perpetual motion. I have wasted no time trying to solve that problem, for it is beyond the power of man.”

While Whitehead was talking he opened a closet and took out a polished steel cylinder a little more than a foot long and about four inches in

diameter.

“That weighs only about a pound and a half,” he said, “and it is worth its weight in gold. Two of

those will be used in the new engine I am building to operate the air propellers. That steel was made to order in England and there isn’t any better in the world. I have carefully considered

aluminum, but decided steel was better, as it is much stronger in proportion to its weight.”

Whitehead became more interested as he talked and told a great deal about his new air ship that was interesting.

“The engines will be the finest in the world,” he declared. “The one that will operate the air

propellers will weigh only twenty-five pounds, but will generate thirty horsepower. Isn’t that a triumph of mechanical skill? This engine, which will be about four feet long, will be placed across

the bow of the boat, projecting over each side just as the engine did in the old boat.”

To show just how the engine would be placed, Whitehead walked into the old ship and showed where the engine had been. As he did this he looked

at the old engine lying on the ground and smiled.

“That isn’t like the new one will be,” he said, “but I built that old one all myself in a cellar. I think I have a right to be proud of it. No, the weight of the engine forward does not overbalance the ship. That

matter of balance was one of the most difficult problems to solve.

-------

Thirty Feet Over All.

“Anybody who knows anything about a bird knows that its greatest weight is at the front, where the

breast are. The engine to propel the ship on land will be in the bottom of the boat. It will weigh about fifteen pounds and will be of about twelve horse power.

“The ship will carry about twelve pounds of calcium-carbide, enough to run it all day. The power is generated by a series of rapid gas explosions. I can produce 150 such explosions in a minute if

necessary. The ship will be equipped with two dry cylinder batteries and a spark coil to explode the gas.

“The gas thus generated will be forced into a compressor, and from there into the cylinders, producing an even pressure. With the gas, a pressure of 500 pounds to the square inch can be produced.

Yes, calcium-carbide is a very dangerous thing to handle, but I am careful. I don’t want to be blown up, atleast not before I perfect my air ship.”

When the gas is forced into the compressor it comes in contact with a chemical preparation, the ingredients of which are known only to

Whitehead: It is the contact with this preparation that produces the tremendous pressure. It is said that dynamite is not as powerful as this new power.

The new ship when completed will be about thirty feet over all the body, or boat, being eighteen feet long and four wide. Though built on the

same plan and propelled by the same power as was the old one, the new ship will differ in many respects.

Instead of canvass on a wooden framework, the boat part will be entirely of wood, with sides about four feet high. The boat, pointed at each

end, is now nearly completed and lies in a shed back of the machine shop.

It will weigh 150 pounds, but Whitehead says that will not be too heavy. Instead of canvass wings and tail, the inventor says he intends to

use sheet steel made as thin as the most skilled workers in Pittsburg can possibly make it. This will be more durable than canvass and will hold more steadily in the wind. The sheet steel, Whitehead

calculates, will weigh less than eight ounces to the square foot. The fan shaped tail will be ten feet long, and, like the sails, made of sheet steel. With all the steel used in its construction,

Whitehead declares the new ship will weigh not much more, if any, than the old one.

“One of the chief reasons men have not been able to fly,” Whitehead said as he looked meditatively

at the parts of his new engine, “has been that they could not make an engine light enough. My engine will create a power greater in proportion to its weight than the muscles of a bird’s wings, but in

a bird the brain that directs the muscles weighs less than an ounce. If a man could use only his brain without the heavy body that goes with it, flying would not be so

difficult.”

Whitehead declares that Santos-Dumont has not accomplished anything remarkable in his air ship.

“The only new thing about it,” he said, “is that he uses a gasoline motor. The balloon, La France, in 1900 made five successful trips out of seven, returning to its starting place. Santos-Dumont has nothing

more than a balloon, a floating machine, I call it. A flying machine, like a bird, must have a greater specific gravity than the air.

----------

Best in Heavy Wind.

“Santos Dumont did not fly around the Eiffel Tower, but floated around. Any great speed with his

machine is impossible, as the big gas bags offer too much resistance to the air. I do not believe he can make any head-way against a wind blowing fifteen miles an hour.

“My machine is entirely different in that respect, as it will fly better in a heavy wind than in light airs. It will fly in any direction too, just as a bird does, regardless of the wind, and will

make fast time, even directly against it, soaring like a bird.

“Yes, there will be some danger in learning to sail my air ship, but I do not think it will be any more difficult than learning to ride a bicycle. After a person can ride well, it becomes second

nature, and one learns to balance it instinctively.

“It is just the same with an air ship. One can control it easily, if he keeps a cool head, and he will soon realize that it is almost part of him. When one has mastered the art, he will be able to

handle my ship as easily as one does a checkerboard.”

There is nothing pretentious about Whitehead’s factory. In fact, one might easily pass it without notice. It is only about forty feet long and

about fifteen feet wide and is rudely constructed of boards. In it, however, is some valuable machinery, and Whitehead says the place is big enough for the present. Adjoining it is a diminutive

engine house about fifteen feet square. In this little shop a dozen men are working on the day force and five at night.

Weimar Mercury, Dec. 12, 1901

Abbreviated, syndicated version:

Dallas Morning News, Nov. 24, 1901, p.10

Even more abbreviated, syndicated version: