Gustave Whitehead - a Short History

Early in 1901, Gustave Whitehead built his 21st manned aircraft. He called it the “Condor”. That summer – more than two years before the Wright Brothers – he made history's first manned, powered, controlled, sustained flight in a heavier-than-air airplane. On March 8, 2013, the world's foremost authority on aviation history, "Jane's All the World's Aircraft", formally recognized Gustave Whitehead's claim. (Later, its editor, Paul Jackson, explained his reasons for doing so in more detail. In 2021, he doubled down on his conclusions, blasting critics in the process.) Upon conclusion of peer review, both houses of the Connecticut legislature unanimously resolved to commemorate Whitehead's achievement as the first person to make a powered flight. The law was signed by the State's Governor and took effect on June 26, 2013.

When the Australian historian, John Brown, was hired to research an aviation documentary for Smithsonian Channel (aired April, 2013), the last book about Whitehead was more than 20 years old. Since then, publicly-funded Whitehead Research Committees in the USA & Germany had continued their efforts. And over 50 million pages of old newspapers had become accessible for online key-word searches. Furthermore, photographic technologies had entered the computer age. This led to some unexpected findings.

Within the first five days of research, known information about Whitehead more than doubled. This caused Dr. Tom Crouch Ph.D., Senior Aeronautics Curator at the Smithsonian at that time, to write he was “incredibly impressed” and Dipl.-Ing. Univ. Hans-Günter Adelhard, Chairman of the Gustav Weisskopf Research Committee in Germany, that it was “atemberaubend” (breathtaking). The research revealed unknown aircraft, unknown public flight attempts (some, years earlier than previously thought), more than 250 unknown newspaper articles, – many of them front page items – and several other surprizes, including the rediscovery of significant facts regarding the long-lost photo of the world's first powered aeroplane flight in 1901. By 2021, more than 2,000 contemporary documents overall and more than 500 news reports of Whitehead's first 1901 flight which had been published in 1901/2 on all inhabited continents had been discovered.

Over the decades, other leading historians have chimed in and recognized Whitehead's pioneering achievements. Research by the Library of Congress's Chief Aviation Historian, Prof. A. Zahm, Harvard University's Prof. J. Crane and, lately, many others has independently concluded that Gustave Whitehead flew before the Wright brothers.)

Whitehead was trained as an engine-builder in Augsburg at a predecessor company of M.A.N.

Gustave Whitehead (born Gustav Weißkopf), son of a bridge-construction engineer, grew up in Germany. At school, he was keenly interested in flight; performed lift-measurement experiments on birds; built models; and jumped off roofs with self-built wings. Orphaned at age 13, he was housed with various relatives before being sent away to a machinist apprenticeship in Augsburg. (It's known that the manufacturer was later absorbed into M.A.N. Co..) Gustave completed his apprenticeship, becoming a trained engine-builder.

Based on his age and later travels, previous commentators falsely assumed he quit his apprenticeship. However back then, German apprenticeships lasted only two rather than the current three years and started younger.

In 1891 he left his home town, saying he was headed for the USA. But when he reached the coast, he met a German family emigrating to Brazil. He joined them and worked on their plantation there. He then became a sailor working on several ships including the Norwegian ship “Gomünd” plying the route between Europe and South America.

In 1893, he arrived in the south of the USA. He was a crew-member on a coastal freighter which was shipwrecked in the Sea Islands Storm off Savannah, Georgia on August 28, 1893. Two weeks later he joined the crew of a Canadian ship and sailed to Southampton, England. He returned to live briefly in Birmingham, Alabama before moving to Baltimore, Maryland where in November, 1894 he again became a crewmember on a trading ship. The ship was heavily damaged in a storm in January, 1895 near New York. After repairs, the following month it was so heavily damaged in another storm that one crewman died and another was severely injured.

Upon arrival in Boston oon April 1, 1895 he quit sailing and began working at Blue Hill Weather Observatory. He soon met James Means, a retired manufacturer, who’d just published a booklet titled “Manned Flight”. In January 1895, Means had announced his intention to found America’s first aviation organization – the Boston Aeronautical Society (which he duly did on March 19, 1895). In the announcement, Means outlined his plans to hire a team of mechanics to build Lilienthal gliders, set up a facility on Cape Cod to perform flight tests and run a flying contest which was to include a “powered flight” category. Whitehead became the Society's first and only Staff Mechanic.

The name "Boston Aeronautical Society" is misleading. It was an international society. All significant researchers on the subject of heavier-than-air flight worldwide were members. These included Otto Lilienthal (Germany), Sir Hiram S. Maxim (UK), Octave Chanute (France), Lawrence Hargrave (Australia) and many others.

Whitehead's first US job was

for Harvard Prof. W. Pickering

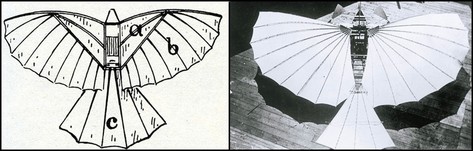

The first President of the Boston Aeronautical Society was the astronomer William Pickering. Pickering discovered both Pluto and Saturn's ninth moon. In aviation, he developed the world's first modern propeller. It was based on the wing of a frigate bird. Whitehead built it for him. (A drawing of that propeller which in all respects is identical to how propellers are explained to modern flight students appears in the 1895 Chanute correspondence. [It is simply untrue that the Wrights invented this principle eight years later.])

According to a written statement by Albert B.C. Horn (one of the mechanics hired) Means and Albert A. Merrill hired him and Whitehead to build Lilienthal-type gliders. Whitehead secured the job because of his previous connection to Otto Lilienthal (Means corresponded with Lilienthal. (Six drafts of Means’ letters to Lilienthal survive – only the drafts remain because the actual letters sent to Lilienthal were in German. This is acknowledged by Means in annotations he made stating “German translation sent”. And when Lilienthal responded, he wrote to Means in German.

At the time, Means did have a German-speaking, full-time employee. Gustave Whitehead not only spoke German but also had a good command of German engineering and aeronautical terms (demonstrated in correspondence with Austrian and German aviation journals). Furthermore, Whitehead was building Lilienthal-type gliders for Means. So, when Whitehead often stated he’d corresponded with, been associated with and studied the work of Lilienthal, the circumstances of his Boston employment would appear to substantiate this. His aircraft’s layout and wing structure certainly show Lilienthal’s influence.

Whitehead was Chief Mechanic for

America's first aviation organization

On many occasions, Whitehead also stated he’d been an “assistant” to Otto Lilienthal. It’s unclear, however, when this contact might have taken place. In a multi-year research effort, historian Col. Walter Prüfert† identified a possible time-frame between October 1893 & July 1894. This has since been narrowed to November, 1893 to February, 1894. This is subsequent to Whitehead's known arrival in Southampton in late October, 1894. Unfortunately, most of Lilienthal’s records were destroyed, making confirmation difficult. Almost all Lilienthal’s visitors rely on their own statement as proof of their visit. However, he made a second trip to see Lilienthal in 1896.

Whitehead himself said that in 1896 he went back to Europe again to see Lilienthal. This was as part of a group accompanying Samuel Cabot which left the USA on April 11, 1896. In a letter to Lilienthal, Means had suggested sending his staff to Germany to learn from Lilienthal. Lilienthal was enthusiastic and suggested that the delegation should consist of young athletes, preferably trained machinists. Whitehead was 22 years old at the time, a trained machinist, a native German-speaker and had the job of building Lilienthal gliders in Boston. [Cabot also visited Germany previously in 1894. It's possible that Cabot and Whitehead met then.

Whitehead built at least 4 gliders

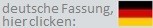

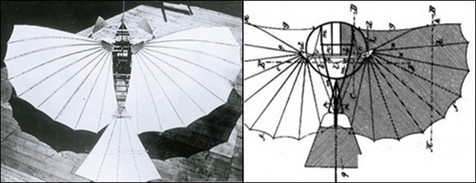

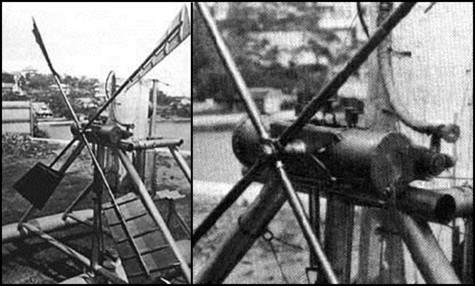

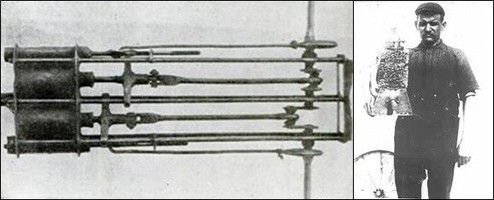

Whitehead built several gliders for the Boston Aeronautical Society. Photos of at least four of them are now known (2021). Some are mentioned in the extensive correspondence of Octave Chanute. One was found in the Australian archives of the aviation pioneer Lawrence Hargrave who corresponded with the Society's General Secretary. Several appeared in contemporary publications including an improved Lilienthal-type biplane glider in 1897. One was a Lilienthal monoplane glider built for Samuel Cabot. Yet another was provided by Whitehead's former colleague, Albert .C. Horn (see below, left). The paddle-propelled glider with a movable empennage used for steering was built for Samuel Cabot and appears alongside Otto Lilienthals 1895/1896 glider in the photos shown below:

Octave Chanute helped finance

Whitehead’s glider construction

According to Horn, the Lilienthal monoplane glider did fly for short distances. Horn stated, Whitehead would have made longer flights if he’d been lighter. Cabot agreed.

Octave Chanute, President of the American Engineers' Association and America’s aviation commentator during that period, helped finance the glider with the more modern wing structure to the tune of $50. Chanute referred to it as the "Weiskopf apparatus". Photos show that it had a two-axis steering system.

Otto Lilienthal was previously known to have sold only one glider to the USA (to William Hearst) and only two sets of original plans to engineers in New York (presumably Augustus Herring) and Boston (presumably S. Cabot). At around the same time, a member of the Boston Aeronautical Society, Charles M. Lamson, had a Lilienthal glider built for him based on original plans, however a newly-found source states that he bought it directly from Lilienthal. Descriptions of how Whitehead’s Lilienthal glider and Lamson’s Lilienthal glider flew are almost identical. And the instructions accompanying Cabot’s set of plans in Boston were all written in German. However, Lamson spoke no German.

Whitehead may be the constructor of the so-called „Lamson-Glider", which would be notable inasmuch as a photo of it adorns the cover of the first edition of Tom Crouch’s book, „A Dream of Wings“, one of the best-known histories of American aviation.

One of the best references for the quality of Whitehead’s work was Samuel Cabot. Cabot initially described Whitehead unfavorably but later changed his opinion, expressing regret when Gustave left in 1897 and hoping Gustave could be hired back again in the future. Indeed, both the Society's J.B. Millet and Cabot himself, did rehire Whitehead briefly in August and September 1897 respectively. (Millet experiemented with kites which were built by Whitehead's subsequent employer in New York)...

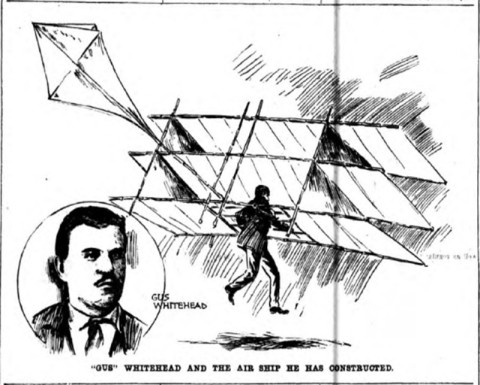

One of the participants in kite flying events at Blue Hill was Edward I. Horsman. Horsman was a professional kite-flyer and well-connected businessman who’d been named by an Act of Congress as an organizer of the 1892 World Fair in New York. Horsman headhunted Whitehead away from the Aeronautical Society to become a member of his “Scientific Kite Team”. The team performed meteorological measurements, aerial photography and public kite & firework displays for New York and other cities. The displays included regular events at Coney Island as well as on Independence Day, Flag Day and at the welcoming of ships into New York and other Harbors, including, for example, the return of US Admiral Dewey after a successful military campaign. Horsman’s team experimented with the lifting-power of kites. Indeed, one of the earliest known newspaper articles mentioning “Gus” Whitehead is an interview with him on the roof of The Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York on Flag Day in June, 1897. At the time, he was operating bright red Horsman box kites and measuring their lift as having attained as much as 100 pounds.

(On later occasions, the Scientific Kite Team performed experiments with kites lifting both sandbags and humans and announced plans to add rudders and a motor. Horsman was a member of the US aeronautical community and even exhibited his kites 10 years later next to Whitehead and the Wright Bros. at the first exhibition of the Aero Club of America in New York in 1906, and again alongside Whitehead at America's first Air Show in the Bronx in New York in November 1908.

Experiments with man-carrying kites were an important part of aviation’s development. The Wright Bros. began kite experiments in 1899 and referred to them as their “Scientific Kite Flying”.)

Whitehead had been hired by Horsman to build a Lilienthal-type, man-carrying kite and add a small, 3 hp gasoline motor with a propeller. However, problems with delivery of the motor ended up in court and may have led to the end of their employment relationship. (In 1897, Horsman also began marketing a keeled box kite called the “Airship”. Horsman obtained a license for that kite's design from one of Whitehead’s former bosses at Blue Hill and its patent owner, Henry Clayton.)

While employed by Horsman, Whitehead continued to test his own manned aircraft. Two are known. The first is referred to in a letter by Samuel Cabot to Chanute dated May 7, 1897 in which Cabot inquires whether Chanute knows of Whitehead’s aircraft “out west”. The other, called “Condor Gus”, was successfully tested by Whitehead during the summer of 1897 at Blue Hill (possibly 1896) and reported internationally.

Whitehead did public flight

displays 1897 in New York

On October 4, 1897, Whitehead invited reporters from at least six New York newspapers along with international news correspondents to an unveiling of his two new aircraft in the courtyard of his residence on Prince Street. One was a bright red tri-plane, box kite glider. The other was a partly-finished biplane with retractable wings (according to him, his 42nd aircraft). Ensuing articles contained drawings of these two aircraft and described their planned motorization with a 3 hp gasoline motor. On October 6, 1897, Whitehead made two public flight attempts at Jersey City Heights witnessed by hundreds of spectators. The attempts were reported across the entire USA, from LA to Boston (Example). One of the spectators was “a young man” who told reporters he’d “witnessed flights by both Chanute and Lilienthal”. (The only known person who fits this description was the New Yorker and aviation pioneer, Augustus Herring.)

After the demonstration, Whitehead put his machine in storage and moved to Buffalo. Six weeks later, on November 24, 1897, he married. When the clerk asked his profession, he replied “aeronaut”. [Some commentators alleged, this is evidence of Whitehead’s tendency to fantasize or self-aggrandize. But research makes it clear, Whitehead would have lied if he’d said anything else.] At that moment he was probably the only person in the world who could honestly state he’d been steadily employed for the past three years building heavier-than-air aircraft.

Whitehead’s qualifications were impressive. He’d been formally trained as an engine-builder; had spent at least four years at sea handling and maintaining sails, rigging, motors and marine propellers; had worked for Harvard’s Prof. Pickering testing kites at the Blue Hill Weather Observatory; possibly translated Lilienthal’s works into English, assisted Lilienthal; built several Lilienthal-type gliders; and had been Chief Mechanic of America’s first aviation organization. He’d then worked for New York’s Scientific Kite Team designing, building and testing a powered, manned kite, all the while building and testing his own flying machines and demonstrating them publicly.

Records at the Buffalo Library show Whitehead spent his time there studying aviation literature including that of Count d’Esterno, whose 1864 aircraft patent bears similarity to Whitehead’s 1901 aircraft. (Not only the configuration but also the number of ribs is identical.)

Whitehead’s handwritten notes made in Buffalo show that the propeller he selected for his future aircraft was very similar to the “Type J” developed by the British aviation pioneer, Hiram Maxim. This wasn’t a simple “air-screw” but a more modern design where the blades were airfoils and their pitch was optimized at varying angles along their length.

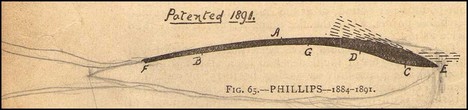

In Buffalo, Whitehead also settled on his wings’ future airfoil. He chose one with its arc peaking near the leading edge designed by the British pioneer Phillipps rather than with a symmetrical arc of the type favored by Lilienthal. Whitehead went even one step further by filling out the concave area under the wing as is now done on modern airfoils (below).

[In a pre-Wright interview - given when Whitehead invited a reporter to fly one of his gliders - he expounded on the 250% lift-increase provided by his curved airfoils.]

Hargrave and Arnot/(Herring)

used Whitehead motors

Whitehead soon introduced a new, wheeled version of his aircraft to the press.

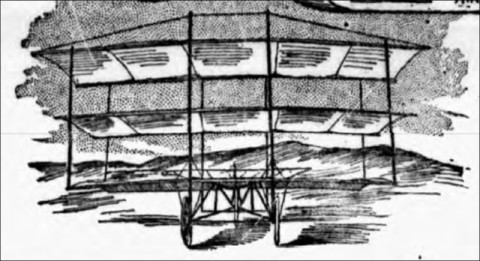

The images and descriptions of Whitehead’s October 1897 and March 1898 aircraft provide a snapshot of Whitehead’s progress in aircraft design. Firstly, the triplane configuration is reminiscent of Hargraves' box-kites which completely replaced the diamond-shaped, so-called “Malay” kites after they first appeared in the USA at the Chicago World Fair in 1893. Secondly, Gustave was still using a symmetrical airfoil (as in the three known Lilienthal-type gliders he’d built for the Boston Aeronautical Society 1895-97). Thirdly, his aircraft had a stabilizing, cruciform tail. This was to become a key feature in the enablement of controlled flight. Existing literature often attributes this invention to others, notably to the young man who’d been watching Gustave’s public flight displays in New York, Augustus Herring or to an early Franch inventor, Penaud.

It’s claimed, Herring’s triplane glider was built in October 1896, however a motorized version wasn’t disclosed until 1898, i.e. after Gustave’s press conference and public displays. It wasn’t until late March of 1898 that Herring, together with Octave Chanute, sent plans for an almost identical, wheeled version to be patented by a middleman (Moy) in London. Construction of the Herring-Chanute Glider was farmed out to Charles Lamson and financed by the Banker, Matthias C. Arnot, for whom Whitehead provably built motors. However, the exact nature of affiliations between Herring, Arnot, Lamson and Whitehead is still unknown.

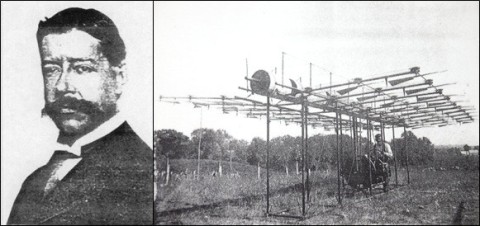

Whitehead soon moved to Pittsburgh. There, according to a stack of affidavits, he fulfilled his prediction and flew an acetylene-Gas-fired liquid-air powered monoplane in late 1899 or early 1900, ending in a firey crash. (In a later interview, Whitehead himself referred to the Pittsburgh flight as "more or less successful".) Despite this, the lightweight engine he’d used impressed other designers. In Australia, Lawrence Hargrave’s 29th engine was a “Whitehead”. He displayed it on July 1, 1901 to the Royal Society of New South Wales. It’s unclear what the connection to Whitehead was. However, since Hargrave was a member of the Boston Aeronautical Society, it could have been from one of the other members or Alexander G. Bell, who visited him in Sydney, James Means, who published Hargrave’s work alongside Lilienthal’s in his 1896 “Aeronautical Annual” or Octave Chanute, or William Eddy, Albert Zahm and Albert Merrill, with whom Hargrave corresponded.

Mid 1900, Whitehead, accompanied by a friend, Louis Darvarich, left Pittsburgh and headed for Boston. They soon changed their destination to Bridgeport.

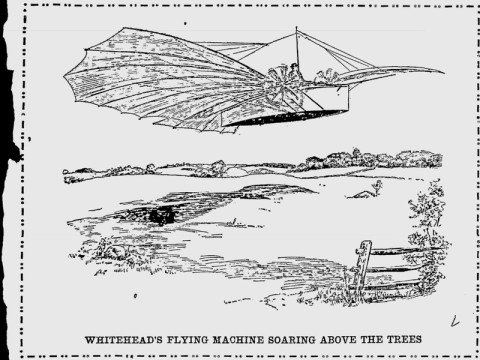

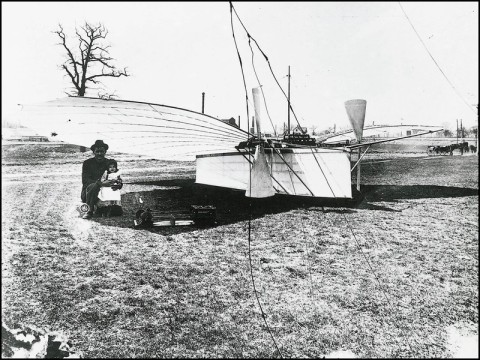

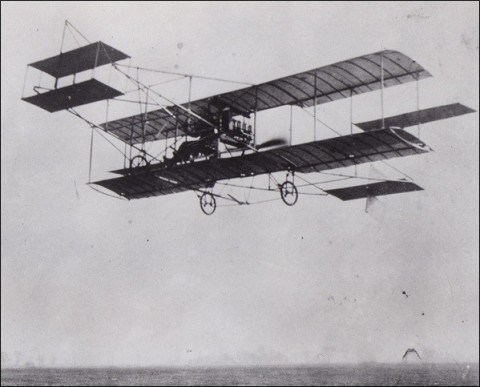

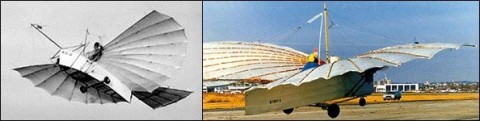

Press coverage of Whitehead resumed in June 1901. Newspapers from Washington to Minnesota and as far away as England and France reported his flight-test of an acetylene-powered, monoplane with sandbags in the cockpit (his 57th aircraft in total and his 20th manned aircraft, he said). The test took place at a site some 1.5 miles from Bridgeport near the village of Fairfield. Two months later, on August 14, 1901, he invited the press to witness his first, successful, manned, powered flight.

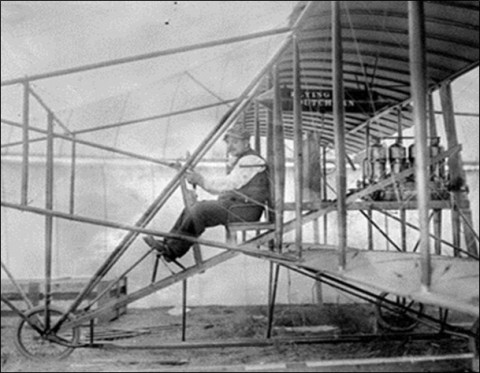

Whitehead's aircraft was "roadable". It's wings could be folded and it had wheelpower for accelerating over the ground which coould also be used for driving on roads. Leaving Bridgeport shortly after midnight, he, his helpers and the press drove the aircraft under its own power 1.5 miles to the same Fairfield site as the previous tests. After rigging and testing the machine unmanned in the pre-dawn light, Whitehead took off at dawn, flying half a mile at a height of up to 50 feet, making a shallow turn along the way to avoid a clump of chestnut trees.

At least 500 newspapers reported

Whitehead’s 1901/1902 flights

So far, over five-hundred newspaper reports of Whitehead’s 1901/1902 flights have been found, many of them front-page news. The reports came from all inhabited continents. [Note: Orville Wright’s main argument in his attempt to discredit what he called “The Whitehead Myth” (August 1945, “US Air Services”, p.9) was his claim that Whitehead’s flight was only reported on a back page of a local newspaper and not anywhere else. Wright also questioned why that paper had waited four days before reporting the story, oblivious to the fact that it was a weekly newspaper which published the report in its next edition. (In his criticism, Orville neglected to mention that the first report by a journalist who had claimed to see himself fly was published in a fortnightly beekeeper’s journal in the following year and that it had been rejected for publication by Scientific American because it was “too far-fetched”.)]

The weekly newspaper, Bridgeport Herald, whose Chief Editor Richard Howell was present, reported Whitehead’s flight on August 18, 1901. The article included an etching (lithograph) based on a photo he’d taken (above). [The search for the photograph is summarized here.] [Note: Howell was well-known for publlishing on the subject of ethics in journalism.]

Whitehead’s plane had 3-axis steering

After the August 14 1901 flight, Whitehead continued to make short flights over the next five months. He then developed a more powerful, diesel engine, calling his new plane “No. 22” and performing even longer flights, one including a full circle. (Flying a 360° circle was the accepted standard for proving an aircraft was controlable in early aviation.) The circular flight was made over the shallows between Charles Island and Bridgeport on Jan. 17, 1902. (Making flights over water was a safety precaution used by the aviation pioneers, Kress (Austria), Langley (USA) and Blériot (France). Others, like Herring, Chanute and the Wrights (USA), used sand dunes to cushion any mishaps.)

Affidavits and statements by 17 people, some of them recorded on audio and video, bear witness to the many powered flights made by Whitehead between August 1901 and January 1902. Parts of the original aircraft, one motor and a large number of photographs still exist. Extensive statements by Whitehead himself survive, illustrating his advanced thinking compared to his contemporaries. And replicas based on the original flew successfully in 1986/7 (in the USA) and 1997/8 (in Germany - click for video, below).

As a result, in 1968, the Government of the State of Connecticut declared Whitehead the “Father of Flight”. On September 14, 1983, the State Dept.’s Information Service made the following press release: „On August 14 1901 a German-American succeeded in the first motorized flight in the history of aviation. [ ] Though Whitehead’s flight happened two years before [ ] the Wright brothers, [ ] it is Whitehead who is the legitimate father of modern aviation.” And on June 25, 2013, after unanimous resolutions by both houses of the Connecticut Assembly, the State's Governor signed legislation withdrawing first flight recognition from the Wright brothers and assigning it, instead, to Gustave Whitehead.

While Whitehead's No. 21 aircraft did have "steering apparatus", not many details are known about it. According to a 1934 affidavit by Whitehead’s brother, John, it had roll-control via wing-warping employing cables attached to the wing-tips.

Statements by family members have low evidentiary weight. Until now, historians have generally rejected this statement and attributed it to sour grapes. After all, the central feature of the Wright Bros.' patent was wing-warping. However, proof the aircraft really did have wing-warping has now been found in a description of Whitehead’s aircraft appearing in the December 1902 issue of "Aeronautical World": “The set or angle of the aeroplanes will be altered and controlled by levers which will regulate the force of compressed air which actuates them in order to deflect the aeroplanes so as to incline or steer a circular course without shifting the position of the ballast or aeronaut.” The article was accompanied by a photograph demonstrating the principle in flight. It showed how the wing warping was linked to the movement of the verticle rudder. [This public disclosure preceded the Wright Brothers' patent application for the same steering arrangement by four months.]

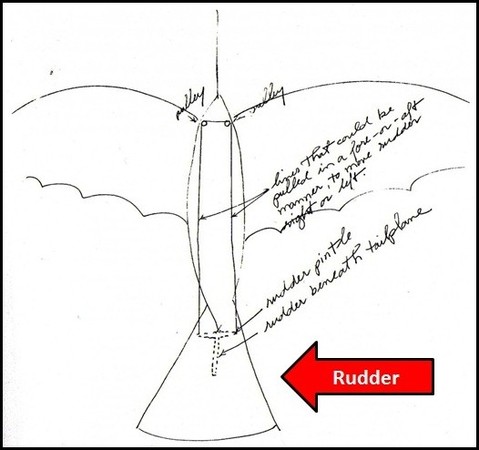

Whitehead's late 1901/early 1902 airplane had a rudder for yaw control. Whitehead himself described it on many occasions. Smithsonian Director, Paul Garber, was kind enough to draw in the rudder in a diagram he himself sketched while interviewing Whitehead’s assistant, Tony Pruckner, in 1966:

Together with the large, vertical elevator, Whitehead’s aircraft therefore had three-axis steering. (Such steering had been invented even before Whitehead. But it’s also claimed by the Wright Bros. citing domestic US patent law which at the time required an invention to be proved by live demonstration.)

Three-axis steering was one of the most important developments leading to the invention of the airplane. Whitehead appears to have had it early on. Articles in New York and Texas refer to setting the wings "at different angles".]

Following the success of the No.s 21 and 22, Whitehead planned a No. 23. Blueprints dated early 1902 show he originally intended to use a canard elevator. It’s not known why he decided against a canard (as later used by the Wrights), but instead chose to use an empennage only. Knowing his reasoning would be helpful to aviation historians. That’s because his monoplane, empennage, tractor-propeller, wheeled-landing-gear configuration was about 25 years ahead of its time. Today, almost all aircraft bear these features. (The plans shown above are among the few Whitehead plans which have survived. However, it’s known Whitehead made precise plans of all his aircraft and motors.)

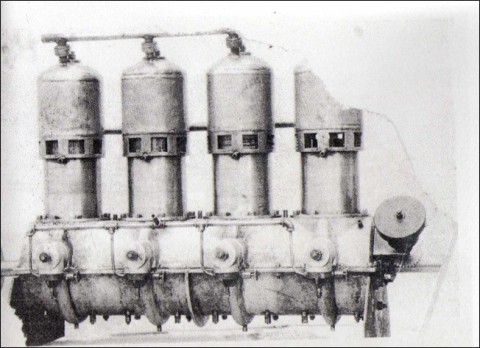

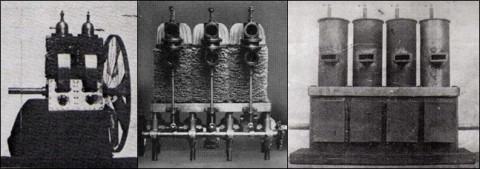

The No. 21 employed several other features of technical interest. Firstly, the smaller of its two motors was 10 hp and provided power to the wheels for takeoff. Upon rotation, its gas-pressure link to the wheels was shut off and was re-routed to the other motor which drove the propellers. A total of 30hp was available for flight. The No. 21’s powerplant was like a steam engine inasmuch as it didn‘t have internal but rather external "combustion" or rather "gas-pressure-generation" (definitions back then weren't as clear-cut as they are today). Whitehead used an acetylene gas flame to heat a pipe through which liquid air was routed toward the motors. The sudden temperature increase of over 400 degrees Celsius created an enormously high air (not steam) pressure. The most important component of the powerplant may have been the pressure relief valve.

The high-pressure gas was ducted first into the cylinders of the lower wheel motor, then briefly into both the wheel and the propeller motors, then - after rotation - solely into the propeller motor. This was done via a lever. The same or possibly another lever appears to have been employed to stretch the fabric surface of the wings tight. This procedure is similar to what modern kite-surfers and paragliders do when they keep their wing devices in a safe, low-lift mode while preparing, then suddenly tighten them for launch. This explains why reports of Whitehead’s flights referred to his machines “shooting into the air”.

After the widespread press coverage Whitehead received following his unmanned test flights in May 1901 and after becoming a media star subsequent to his manned flights in August 1901, Whitehead was besieged by opportunists hoping to cash in on his invention.

Prof. Langley sent spies

The first was H.S. Le Cato from Philadelphia who, after first watching the airplane fly, offered Whitehead a six-month contract to display it at Atlantic City. Days later it was loaded onto a railcar and shipped there. While at Atlantic City, the Smithsonian Institute sent two spies, Traylor (a clerk and Prof. Langley's personal secretary, below center) & Hodge (an ethnologist, below left) to examine the airplane. Written instructions were issued by the Director, Prof. Langley’s assistant, Charles Manly (below, right) asking that measurements of Whitehead’s machine be made surreptitiously.

The Wrights deny coming

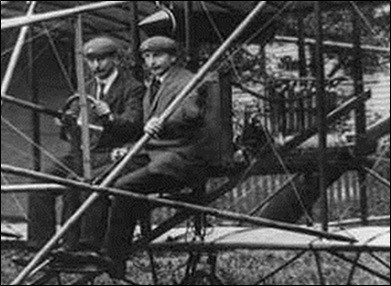

The Wright Brothers were among the next visitors. After receiving a July 1, 1901 letter from Octave Chanute recommending a 10 HP, 30 lb. Whitehead motor (which Whitehead was building for M.C.Arnot and for Prof. C.E.Meyers), Wilbur replied on July 4, 1901 as follows: “The 10-horsepower motor you refer to is certainly a wonder if it weighs only thirty lbs. with supplies for two hours, as the gasoline alone for such an engine would weigh some ten or twelve lbs. thus leaving only 18 or 20 lbs. for the motor or about two lbs. per horsepower. Even if the inventor miscalculates by five hundred percent it still would be an extremely fine motor for aerial purposes”. At the time, the Wrights were actively looking for a motor. They invariably followed Chanute’s advice (as they’d done previously by hiring Herring, Spratt and Huffaker). Three witnesses attested to their visit under oath*. Yet, the Wrights denied visiting Whitehead or even Bridgeport before 1909.

Circumstantial factors appear to support their visit. The Wrights had a good friend in Bridgeport. He was the submarine inventor, Simon Lake, with whom they discussed their glider and their patent options before their claimed 1903 flight. The Wrights were in almost constant contact with aviation pioneers such Chanute and Herring. It’s hard to believe the only one they ignored was Whitehead, especially since his experiments had been so widely reported in "Scientific American", Prof. Langley was spying on him, Chanute was recommending him and he was producing motors for their competitors, Herring/Arnot.

For aviation experts, perhaps the most important discovery about Whitehead may not be the additional evidence of his first flight. In Dec. 1902, Whitehead published a precise description of the combined wing-warping/rudder mechanism on his airplane in "Aeronautical World" - just like in the Wrights' patent. But Whitehead disclosed it almost 4 months before the Wright brothers applied for their patent (on March 23, 1903). The significance of this is that the Wrights' whole claim to preeminence rests on their claim to have both discovered and practically applied a wing-warping system combined with rudder movement first. (Contrary to popular belief, in their court proceedings, the Wrights freely admitted they weren't the first to have invented a powered airplane.) Undeniably, Whitehead was the first to publish and practically apply a system of wing warping combined with rudder movement.

Chanute’s mid-1901 letter to the Wrights offers yet another snapshot of Whitehead’s status in the aeronautical community. Long before his famed August 1901 flight, he was not only providing motor ideas to Hargrave in Australia, but building Motors for Arnot/Herring’s airplane, Meyers’ airships and possibly for many other efforts too.

When Le Cato’s promised contract in Atlantic City didn’t materialize, Whitehead returned to Bridgeport where he had been working with the Texan, William D. Custead.

Custead promised to invest $100,000 but soon left when Whitehead refused to share details about his powerplant. However, Custead did buy a motor from Whitehead and became one of the first dealers for Whitehead motors.

Whitehead’s most fateful visitor was Herman Linde, a German immigrant who made his living as a Shakespearean actor. Needless to say, things didn’t add up. Linde agreed to finance Whitehead’s project and built a new workshop. Encouraged, Whitehead himself took out a $1,700 loan and wrote to his family in Germany that he was now the owner of an airplane factory. However, secretly, Linde planned to take over the venture and started colluding with workers. Mid-January 1902, right when Whitehead was short of cash, Linde withdrew support and announced the formation of his own aviation company, and refused to pay any more bills. Linde was later convicted of multiple criminal offences and admitted to an insane asylum. But that came too late for Whitehead. He was now broke. Four to six unfinished aircraft remained in Linde’s workshop to which Whitehead no longer had access.

Whitehead's No. 22 aircraft was left outdoors for the rest of the winter for lack of a place to store it, becoming unserviceable as a result. In April, Whitehead’s brother, John, arrived and contributed some of his savings. But it wasn’t enough. Soon, John left. It was then that Whitehead decided to stop building his own airplanes. Clearly, no-one was willing to actually pay for them. From then on, he would only build them for others. Instead, he concentrated on selling motors. These were immediately in high demand, especially among airship and flying machine builders. Having thus secured his livelihood, he spent the next few years (until 1905) building a house for himself, his wife and his nearly four year old daughter, Rose.

This decision led to Whitehead becoming a central figure in the early years of US aviation. He quickly made a name for himself as an aviation supplier. As early as 1902 the “Automobile Trade Magazine” reported that customers could order lightweight kerosene, gasoline, acetylene, steam and gunpowder motors along with dirigables and airplanes from Gustave Whitehead in Connecticut. In 1907 he was opening speaker at an aeronautical congress in New York attended by many of the aviation pioneers of the time.

Whitehead became a major

motor & airframe supplier

At the 1904 World Fair in St. Louis, Whitehead exhibited one of his motors. The winning dirigible at the flying machine contest held there was Thomas Baldwin’s “California Arrow”, flown by Roy Knabenshue. It, too, was equipped with a Whitehead motor – at least that’s what a qualified aviation journalist wrote after examining it. American historians later claimed it was a Curtiss motorcycle engine, which isn’t necessarily a contradiction. Publicly disseminated drawings show an inline Whitehead motor was later replaced by a V-type Curtiss motor. Furthermore, two sources report Whitehead built aircraft motors for Curtiss, which may explain why many early Curtiss and Whitehead motors looked so similar. And when the Curtiss-Herring Co. went bankrupt, Whitehead's motor distributor, George Lawrence, was one of the creditors owed money by the Herring-Curtiss venture. (Knabenshue went on to make one of the first dirigible flights over New York and become chief pilot of the Wright Exhibition Team. Baldwin became Vice President of the Aero Club of America. And in 1908 Baldwin’s airship and the Wright Flyer won the US Army’s Contest to select a military flying machine.)

Yet another Whitehead motor was present in St. Louis. It powered Prof. Carl E. Meyers’ Sky Cycle. Meyers was the balloon supplier for the US Weather Service and the US Army Signal Corps. The Sky Cycle had been patented in 1897 and sold successfully – as the name suggests – as a pedal-powered airship. Just four days after the July 1901 Chanute-Wright correspondence, a New York newspaper reported that the 30 lb./10 hp motor the Wrights were interested in was to be installed in the Sky Cycle so it could compete in St. Louis. At the contest, the local press reported on the motor’s use. The Sky Cycle went on to become one of the first commercially successful aircraft ever. For many years, Meyers sold it via classified ads appearing in technical magazines across the USA, offering single, twin, three and four cylinder, powered versions.

The world record balloonist, H.E. Honeywell, also ordered two Whitehead motors. In 1904, the physics professor, John J. Dvorak, examined Whitehead’s work and in a front-page newspaper article publicly declared Whitehead to be ahead of all other aviation pioneers. He, too, hired Whitehead to build a motor. In summer, 1905, Whitehead installed an 18-20hp motor in the "Flying Machine" of Israel Ludlow. Ludlow's pilot was Charles K. Hamilton from Connecticut. In 1906, Hamilton moved on and later became a Curtiss Show Pilot. He was replaced by J.C. ("Bud") Mars who later also joined the Curtiss Team. Whipple S. Hall of Fresno, California was another Whitehead motor customer.

Henry A. House, former assistant to Hiram Maxim, was involved in Whitehead's projects, living just half a mile from Whitehead's workshop. He was photographed next to Whitehead in front of his airplane on May 30, 1901.

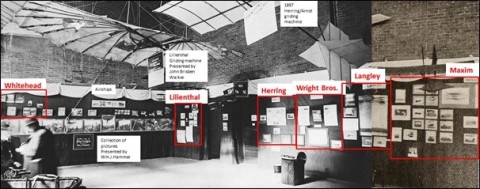

1906 was a year in which Whitehead’s prominent position in the American aeronautical community was clearly apparent. A detailed analysis of panorama photos taken at the first exhibition of the Aero Club of America in January 1906 revealed not only the location of the long lost photo of Whitehead’s No. 21 in powered flight (as reported by Scientific American at the time) but also an indication of Whitehead’s status among his aeronautical contemporaries. The aviation exhibition was housed in a single room around which visitors proceeded in a clockwise manner. It started with ten photographs of Whitehead’s aircraft and motors. The very first ones (at top, left) showed his 1901 flight (according to Scientific American). Next, they saw thirty-three photographs of balloons and dirigables including those of Knabenshue and Santos-Dumont. Following them were eight photographs of Lilienthal’s gliders, six of Herring/Arnot’s glider, six of the Wright brothers’ gliders & kites, eight of Prof. Langley (including one of his flying model) and twenty of Hiram Maxim’s powered airplane. As a highlight, Baldwin‘s previously Whitehead-powered „California Arrow“, in which Roy Knabanshue had performed a flight over New York just a few months previously, was on display.

In 1906 aviation,

Whitehead was pre-eminent

It wasn’t until September 1, 1908 that the Wright Brothers first released a photo of their claimed 1903 powered flight in Century Magazine. (The first photo of them flying was captured by a reporter hiding behind a sand dune at Kitty Hawk on May 20, 1908, just days after they went back to Kitty Hawk on May 6, 1908 - returning for the first time since 1903). Up until then, they only showed photos of their kites and gliders (and the crank-shaft of their motor, resting on a stool). At the January 1906 exhibition, Herring/Arnot didn’t show any photos of their powered flight either. The only exhibitor besides Whitehead who showed powered flight was Prof. Langley with his scaled model. It’s therefore understandable why the photograph of Whitehead’s 1901 manned, powered flight was given a place of such prominence at the beginning of the exhibition. After all, only Whitehead and dirigible airships were able to freely control their movement through the air.

Ironically, during this transitional period (December 17, 1903 until May 20, 1908), the Wrights faced the same dilemma as Whitehead did in the years 1906-2012 when people asked, “where’s the photo?”.

The Feb. 10, 1906 Editorial of "The New York Herald" (Paris Edition) wrote about the Wrights and bore the headline: “Flyers or Liars?”

Whitehead's stature appears to have reached a zenith in December 1906 at the second exhibition of the Aero Club of America. There, he had three newer motors and two propellers along with the original fuselage and motor of his 1901, "No. 21 Condor" aircraft on display. The aircraft was clearly labelled as having flown. (The Wrights, on the other hand, only showed their motor.)

Whitehead Motors Powered

the First US Military Aircraft

In 1907, Whitehead was registered as one of the participants in the flying events at the World Fair in Jamestown, Virginia. It's not known if he himself displayed anything there. But one of his motors was accompanied Israel Ludlow's Whitehead-powered "Flying Machine". The construction of that machine had been financed by the US Navy. It was displayed as a hydroplane in Jamestown (without the motor), then with wheels at the Gordon-Bennet & Scientific American events in October 1907 in St. Louis (which were part of the Expo). Also in October 1907, Whitehead was one of the lead speakers at a national aeronautical congress in New York.

A Whitehead-Powered Airplane Took

Off on the Smithsonian's Front Lawn

Development of the Ludlow aircraft for the US Army Signal Corps.' trials at Fort Meyer continued until 1908. During tests just before the trials commenced, Ludlow's Whitehead-powered aircraft got briefly airborne. The test location was the front lawn of the Smithsonian Institute on the Washington Mall. The flight was only brief because the propeller shaft broke. Ludlow admitted ignoring Whitehead's advice about using the correct fly-wheel and had instead replaced it with a lighter one of less than half the correct weight.

Alongside his brisk motor business, Whitehead took on aircraft construction jobs. One of his customers was Wild-West hero, Buffalo Jones, for whom he built an ornithopter. His main customer was "Scientific American"’s Aviation Editor, Stanley Yale Beach, whose father edited – and grandfather founded – that magazine. Beach was also co-founder of the New York Aeronautical Society. Whitehead built at least three aircraft for Beach. However, Beach had his own ideas about aircraft design. In one incident the two argued so vehemently that Beach had Whitehead arrested. The disagreement arose when Beach hacked off the upper wing of a biplane to make it a monoplane (which he believed would fly better). That led Whitehead to confiscate the engine – presumably for safety reasons. Ultimately, Beach did build a monoplane based on Bleriot's design. One of the three engines successively installed in it was a 4 cylinder, 25hp Whitehead engine. In another incident, Whitehead, his brother, John, and a certain William J. Snadecki built a 200hp, V8, engine for a racing boat (later developed into an aircraft engine) which Beach insisted on testing. John Whitehead wrote that Beach overrevved the engine and ended up sinking it and the boat it was on in Long Island Sound. (In unrelated incidents, Beach ran over and killed a pedestrian in Bridgeport, then refused support for his wife and child causing his father to cut off all funds, thus ending his aviation experiments.)

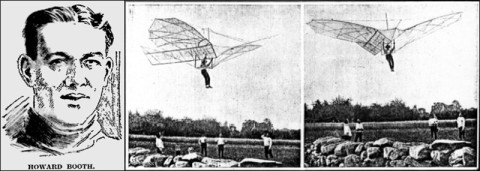

A Whitehead glider competed at the very first air show of the New York Aeronautical Society in Morris Park in 1908. It was built for Louis R. Adams, President of the Long Island Automobile Club and Vice President of both the New York Aeronautical Society and the Aero Club of America. It was flown by Bridgeport resident, Howard Booth.

In 1909, all winged, heavier-than-air aircraft in America were grounded by injunctions obtained by the Wright brothers to protect their patent. If an aviator wanted to continue flying his own airplane, he was required to buy a Wright License which cost more than $25,000. The only other legal option was to buy the Wrights' canard-biplane-pusherprop invention which most were unwilling to do – especially Glenn Curtiss. (Curtiss ended up ultimately taking over the Wright Aircraft company when it failed and modernizing its aircraft designs.)

Whitehead’s final aircraft construction job was for a helicopter (which didn’t violate the Wrights’ patent). He built it for the President of the Aeronautical Society of America, Lee S. Burridge. That was shortly after he'd stopped flying altogether when, in 1910, the monoplane he was piloting crashed into a bridge, crushing his rib-cage.

Starting in 1910, Whitehead’s motor business boomed all the more. He continued building motors for retail customers like C.S. Wilson, who successfully competed in events in his Whitehead-powered biplane. But he also wholesaled his engines to dealers and aircraft manufacturers. One of them was America’s first successful, commercial aircraft builder, Charles & Adolph (C. & A.) Wittemann. (Charles was co-founder of the New York Aeronautical Society). When asked later about Whitehead’s abilities as a motor-builder, Charles Wittemann described him as “a genius”.

Both C.W.Miller’s & Barberton Aviation's airplanes, were built by C. & A. Wittemann and equipped with Whitehead motors.

Other Whitehead motor dealers were Cleve Shaffer, President of the Pacific Aero Club and the West Coast’s first commercial aircraft builder, and Geo A. Lawrence, an international aircraft and aviation motor dealer who advertised Whitehead motors across the USA and even in Europe. (Lawrence also built a hydroplane powered by a Whitehead motor.)

Not all of Whitehead's motors were for aircraft. For example, Buffalo Jones bought Whitehead motors for both his aircraft and his irrigation equipment.

So far, over forty different types of Whitehead motors have been identified. A steam engine and parts of an eight-cylinder engine exist to this day. Whitehead’s daughter, Rose, remembers there were sometimes more orders for motors than she could hold in her hands when she fetched the mail. She also remembers her father returning more than 50 orders (including down-payment checks) on one single day due to overcapacity.

Even Whitehead’s enemies grudgingly acknowledge his abilities as a motor builder. There are many hints as to where Whitehead’s motors were used in the years 1902-1915. In this regard, Whitehead research is at an early stage. However, that’s not the main issue.

On October 15, 1964, Charles Wittemann made a written and tape-recorded statement under oath in which he declared he’d spent a week working alongside Whitehead in his Bridgeport workshop, had examined Whitehead’s 1901 airplane and found it capable of performing the claimed flight. The significance of Wittemann’s statement is not only his personal knowledge of the facts but also his legal standing. Wittemann was appointed by US President, Woodrow Wilson, as America’ Chief Aviation Expert in WW1. His expert witness statement therefore has added evidentiary weight. Another aviation and motor expert, Carl Dienstbach, made an earlier examination of the same engine. Both reports are here.

Although existing evidence eliminates any need for circumstantial corroboration,

- the proven airworthiness of both the Whitehead engine and the Lilienthal wings

employed in the No. 21 aircraft, and

- successful flights of two replicas of the No. 21 (1986, USA and 1997, Germany)

lend further support to Whitehead’s claim to have successfully flown such an airplane in 1901.

Whitehead pioneered powered flight

and was prominent in early aviation

In summary, Gustave Whitehead was instrumental in the transfer of Otto Lilienthal’s advanced aviation knowledge to the USA in 1895-6. In 1901, Whitehead built and flew the world’s first manned, powered airplane in sustained flight which, in various iterations, had three-axis control. And his motors played an important role in pre-WW1 US aviation. His decision to become mostly a supplier rather than continue development of his own aircraft was based on his lack of funds and his devotion to his young family. Rather than detract from his legacy, it shows he was not only a talented inventor and mechanic but also a decent human being.

History of Whitehead Critics

The last eight decades brought forth the occasional Whitehead critic. For a nostalgic look back, click here.